In the beginning

Approximately 200 million years ago, a substantial portion of Europe and the Middle East was submerged as part of the Tethys Sea.

During this time, a process of carbonated sedimentation began, caused by the accumulation and deposits of marine animal skeletons and shells at the sea bottom. This process continued for approximately 175 million years, gradually forming horizontal sediment layers with varying thicknesses, accumulating to thousands of meters.

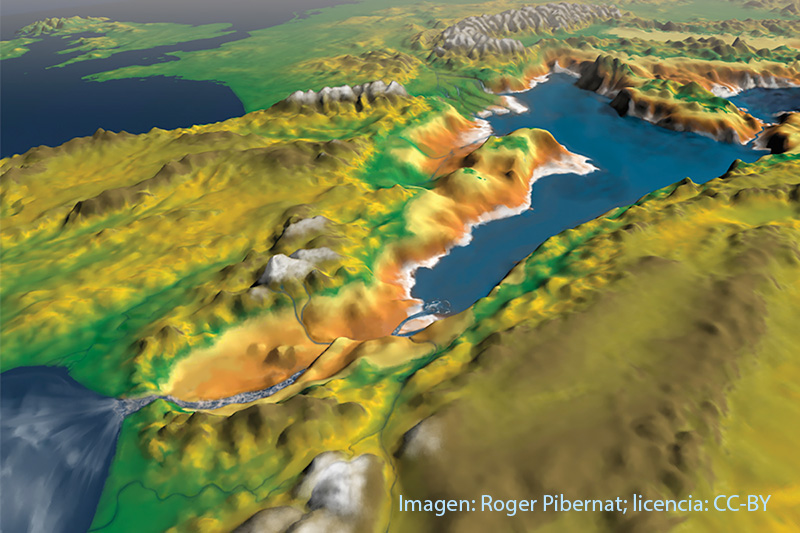

Fast forward to the beginning of the Miocene period, approximately 21 million years ago, when the African and European plates started to converge. This dramatic event caused the Earth's crust to rise, particularly leading to a counterclockwise movement of the Iberian plate (forming the Bétic mountains) and a clockwise movement of the African plate (forming the Rif mountains).

As the process continued, in what was a very fast geological event, the plates eventually closed off access from the Atlantic Ocean and created a land bridge to Europe.

Five million years ago, the flow of water from the Atlantic Ocean all but stopped, causing the Mediterranean Sea to dry up. The water left behind evaporated, leaving salt crystals precipitating at the sea's bottom. This extended dry period lasted for hundreds of thousands of years. As a result, the Mediterranean became almost uninhabitable for marine species, which either migrated or died due to extreme environmental conditions, such as excessively salty or shallow water.

About two million years ago, when the waters of the Atlantic began to re-flood the Mediterranean through the strait, the difference in level between the two seas caused the incoming water to produce rapid erosion, deepening its own channel and triggering what would have been the most significant and most abrupt flood known to us on Earth. The erosion valley left by this process on the seabed is at least 200 km long, about 8 km wide and several hundred metres deep.

The feedback between the incoming water flow and the size of the inlet channel, enlarged by erosion, led to flows of up to 1,000 times the current Amazon River, and the Mediterranean could have filled in just two years at a rate of up to 10 meters per day.

Today, the African and Eurasian plates are still moving and approaching in a WNW-ESE direction at about 5 mm/year, which geologists believe will mean the Mediterranean will dry out again. Fortunately, though, this is about 20 million years away.

This proximity to North Africa, along with the absence of the previous ice age 20,000 years ago, ensured that the Iberian Peninsula was not only a refuge conserving a diversity of birds and plants that disappeared in other regions of northern Europe, but also the genetic diversity of the human populations existing at that time.

The Arch of Gibraltar

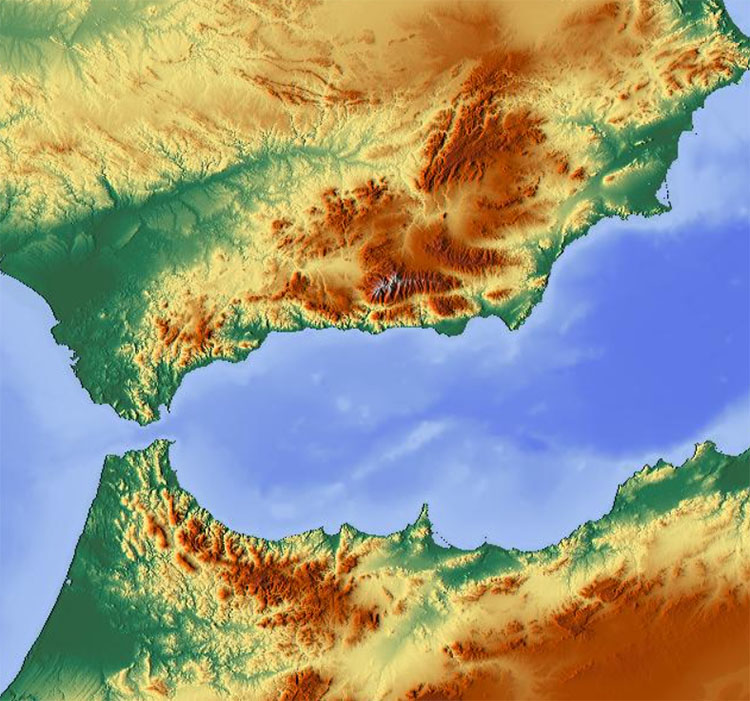

Together with the Rif Mountains in North Africa, the Betic Mountains form the westernmost segment of the Mediterranean Alpine orogen (a belt of the Earth's crust involved in the formation of mountains).

The Bétics constitute all the mountainous reliefs in the south of the Iberian Peninsula, extending from the Gulf of Cadiz to the coast of Alicante and the Balearic Islands. They have been termed the 'Arch of Gibraltar', with a length of about 620 km and a maximum altitude at the Mulhacén peak of 3,478 m.

The Bétic System is divided into the three sub-chains, and from North to South: Prebétic, Subbétic, and Penibétic. It is the Penibétic chain that all of our walking is in.

Although initially, all the depressed areas within the mountains were flooded by the sea, gradually, as the mountain range rose, the sea withdrew. Some became drainage basins where rivers flowed, and important lakes formed.

The Penibétic Mountains and the Central Limestone Arch

The Penibétic range, the southernmost of the Bétics, stretches 500 kilometres from Cadiz to Murcia and is 65 kilometres wide at its widest.

This range is not continuous and comprises a complex system of mountains and lesser ranges.

Our walks focus on the Cordillera Antequerana, Sierra de Enmedio, and the Sierras Tejeda, Alhama, and Almijara mountains. These stretch for over a hundred kilometres, from Teba in the west to La Herradura in the east, and the forests and valleys, along with villages and towns within them, offer some of the best walking in Andalucía.

The Central Limestone Arch, which extends 50 kilometres in an east-to-west direction from the port of Alazores to the Gaitanes gorge, divides the provincial territory into two sectors, serving as a climatic border between the Antequera Depression to the north and the Valle del Guadalhorce and Axarquía, to the south, and at the same time it serves as a link between the Sierra de las Nieves, to the west, and the Sierras de Tejeda and Almijara, to the east.

Great walks along the Limestone Arch include El Chorro, El Torcal, Hondonero Meadow, Chamizo, Tajos de Gomer and the Pico del Vilo.

The landscape we traverse is predominantly composed of sedimentary limestone and dolomite rock, with numerous examples of karst formations. In particular, the unforgettable El Torcal Natural Park has one of the most accessible displays of erosion.

Signs of erosion are always present during our walks, whether in individual rock formations, we may walk past or the entire landscape around us. The Sierra de Loja, a 210 km2 limestone massif, has the highest concentration of sinkholes in Andalucia and is a stunning and intricate, far-reaching landscape.

When we walk the Caminito del Rey along the Gaitanes Gorge in El Chorro, we see the full power of erosion on the limestone as we navigate the path halfway up the 300-metre vertical rockface.

By the end of your stay here, you should be able to quickly identify features such as grikes, clints, pancakes, and runnels.

Interesting places to visit

I have compiled a short list of the Penibétic mountains' geological highlights, which you can visit during one of our walking holidays (links included).

Tajos de Molino, Teba - A spectacular gorge eroded over millions of years, set against the backdrop of the Guadalteba Valley.

Gaitanes Gorge, El Chorro - Home to the Caminito del Rey, this canyon stretches several kilometres.

Arabic Steps, El Chorro - Above the Gaitanes Gorge, spectacular rockfaces rise from the valley floor.

El Torcal Natural Park - One of Europe’s most impressive karst limestone landscapes.

Cuevas de San Marcos - This site is located outside the Penibetic range, but it is significant due to the geological aberration formed by the shift in the Earth's crust.

Hondonero Meadow - Set under the shadow of the Sierras de Camarolos and Jorge, with a view of the Antequera Depression.

Tajos de Gomer - An impressive limestone mountain on the southern side of the Central Limestone Arch.

Pass of Zafarraya/Sierra de Loja - A natural pass through the mountains, leading to the southern approaches to the Sierra de Loja, one of the most important karstic areas in Andalucía.

Almanchares Canyon - This deep canyon, fed from the southern face of La Maroma, the highest mountain in Malaga, has impressive fluvial geomorphology.

As you may imagine, a wealth of information is available on the geology of southern Spain. The purpose of this article, however, is to provide a brief introduction that helps better understand how geology has shaped the landscape we will walk through.